Down Under

By the summer of 2012, I was living in Australia with my family. Looking back on it now, Shannon says, “We could do it, so why not? Our time in Australia was one of the best things we ever did.” Being in Australia gave me time to switch gears from business to being a full-time dad. Shannon and I assisted with our boys’ surfing lessons, helped with their homework, and read them stories.

The company at that time was worth about $12 billion, so it put our personal net worth at about $4 billion. I was also still chairman of the board. I was obviously very interested in lululemon’s performance in the market because every time the stock went up or down a dollar, our net worth went up or down $40 million.

Since our departure, Shannon and I had stepped away from much of what was happening at the company. I hadn’t been a part of any of the changes to the lululemon product or to the restructuring of the business, but even from afar I could see their struggles.

There was a conflict between the company’s short-term incentive plan and my own plan as a long- term stockholder with a 50-year outlook. A CEO’s personal wealth lies in their ability to sell their options on a high and to inflate their personal brand to negotiate the maximum compensation at their next job. Christine and Bob had both done this. Bob at least had been transparent about it. When Christine did it, it caught me off-guard, and it hurt.

In Good to Great, Jim Collins illustrates how every change to a process has the flywheel move more slowly. Lululemon developed systemic atrophy, moving it from great to good. A company of lululemon’s size is made up of thousands of processes. If one process changes, then someone needs to understand how to change the three pieces that fit into it. If a CEO changes 20 processes – but doesn’t change the three contributing processes for each of those processes – then the system breaks.

A fabricated story that could have happened to a founder and largest shareholder

The following fictional story did not happen because if it had, the legal ramifications would be immense.

Let’s say a founder discovered a major quality control problem that made an entire production run of a style unusable. The number of garments to be recalled would materially upset the previous year’s financial statements. The company would have to destroy the garments, the bonuses for management would have to be clawed back, and the audit committee would have to report the error to the public.

What if the QC problem was twice reported to the CEO without action? What if, after the CEO would not take action, the founder gave the evidence to the Chair of the Audit Committee? What if the Chair of the Audit Committee thought the best route was to figure out how to undermine the founder rather than deal with the issue as a business challenge?

In this situation, the founder finds himself between a rock and a hard place. If the founder reports the issue to the SEC and regulators, then a five-year legal case could ensue, dragging the founder into legal discoveries and court cases that could go on forever. The amount of travel to handle the legal issues would mean time away from his family and time not focused on moving the company forward.

Should the founder forego his and the company’s integrity so as not to be pulled into a time-wasting legal sinkhole? Maybe. Is the founder out of integrity by knowing, as founder of a public company, that the error should be reported? Absolutely.

Hopefully, this difficult scenario helps other founders and large shareholders understand what could happen. But fictional stories are fictional stories.

Trouble Getting Closer

As 2012 turned to 2013, our sales were continuing to increase 30 percent per year.1 The global demand for athletic apparel was exceeding our ability to supply it, and increasing sales easily hid the underlying issues.

In mid-March 2013, the so-far unquantifiable problems in our quality came to a very public head.

“Lululemon Has a See-through Yoga Pants Problem.”2 That was the headline in the Corporate Intelligence section of the Wall Street Journal on March 18, 2013. On the same day, Business Insider ran a story entitled: “Lululemon Pulls Stretchy Black Pants Because They’re Too Sheer.”3 Then the CBC ran this a day later: “Lululemon Recalls Pants For Being See-through.”4

Similar stories ran in the National Post, the Globe & Mail, the Daily Mail, Bloomberg, and Forbes, among many others. We had to announce a massive recall of our signature women’s Luon pants, based on the now-infamous transparency problem. Women’s Luon pants made up 17 percent of our total inventory, and the recall was likely going to cost $60 million in lost sales.5

Jill Chatwood recalls: “I was on maternity leave, travelling in Australia with my husband and children. We stopped in for a visit at the house that Chip and Shannon were renting. It was clear to me that Chip had some concerns with how the product team was operating. I confirmed for him that quality was not as strong a focus as it had been in the past and that I, too, was concerned.

“Lo and behold, within weeks of that conversation, it was discovered that the consistency and quality of our key fabric, Luon, was compromised. The ‘sheer pants’ emergency was in full swing. Pressure to make financial numbers was winning out over commitment to quality.”

A lifetime of research into how to make best-in-the-world non-transparent black stretch pants all came undone in an instant.

Christine blamed Eclat Textile, which had grown to become our number one fabric and manufacturing partner and fired our Chief Product Officer.6 Shifting blame is a standard Machiavellian move to protect the incompetent, and it was Christine’s go-to move in a situation of survival.

According to Christine, the sheerness issue was Éclat’s fault, plain and simple. I was mortified for lululemon. Solving for sheerness was the functional reason that I started lululemon in 1998. And, amid this uproar, the conversations of other big quality issues that I had previously brought forward evaporated entirely.

Around this same time, we received an email from Lucy Lee Helm, general counsel for Starbucks. I was a carbon-copy recipient of the e-mail, as was Michael Casey. The letter was addressed to Christine, and summarized Starbucks’s concerns about a recent interview Christine had given with ABC’s Katie Couric only a few weeks earlier:

Dear Christine,

On behalf of Starbucks, I want to express our deep concern about your troubling comments on the “Breaking the Glass Ceiling” segment of the nationally syndicated Katie Couric television show. What we heard you say about Starbucks personnel practices, and your own career opportunities with Starbucks, are disparaging and simply untrue.

During the course of your interview with Ms. Couric, you described your experiences at Starbucks and, specifically, that the company gave you jobs that “nobody else knew how to do” and that the company “tried to sideline you when you had children.” You described one experience in which you perceived you were treated differently than a male colleague and agreed with Ms. Couric that that was a “fairly typical moment” in your Starbucks experience. Your comments imply that your considerable success at the company was somehow limited based upon your gender.

This characterization is not only inaccurate and untruthful but disparaging of Starbucks and its partners. Starbucks appreciates your many contributions during your employment with the company but frankly you, too, were provided with significant opportunities. Indeed, you progressed significantly in your career at Starbucks over 20 years, from administrative assistant to senior executive levels. You had many leadership roles and received opportunities for learning and advancement across the organization. To suggest that Starbucks somehow mistreated you or failed to accommodate your schedule because of your gender is a serious distortion of the record and one that does a great disservice to Starbucks, its partners, and its legacy of progressive personnel practices. And it does not accurately reflect the career path you achieved at Starbucks, which you have successfully leveraged to “catapult” to an impressive position at lululemon.

Starbucks would prefer to avoid a debate or dispute with you over your statements. But we cannot allow inaccurate, misleading and frankly disparaging comments about the company, its partners, and its human resource practices to go unanswered.

Sincerely,

Lucy Lee Helm

Executive Vice President, General Counsel and Secretary

cc: Howard Schultz Dennis J. Wilson

Michael Casey7

With Michael Casey as one recipient of the letter, I thought the support for Christine would finally collapse. After all, the number one job of a board is to hire a CEO and ensure a CEO succession pipeline is in place. I think the Board was afraid that firing the CEO would draw publicity that would adversely affect lululemon’s short-term share price and the directors’ reputations.

A meeting was held in Sydney, Australia. At the end of the meeting, the Board asked me to come back to Canada to try to help fix the problems. With our Chief Product Officer gone, the lululemon product team also phoned my wife Shannon asking her to come back and help.

Asking us to come back was the Board’s directive to Christine. She was to make space for us in the company because of all the challenges they were facing. Shannon and I agreed right away. We would absolutely go back. We were lululemon’s biggest cheerleaders – we always will be.

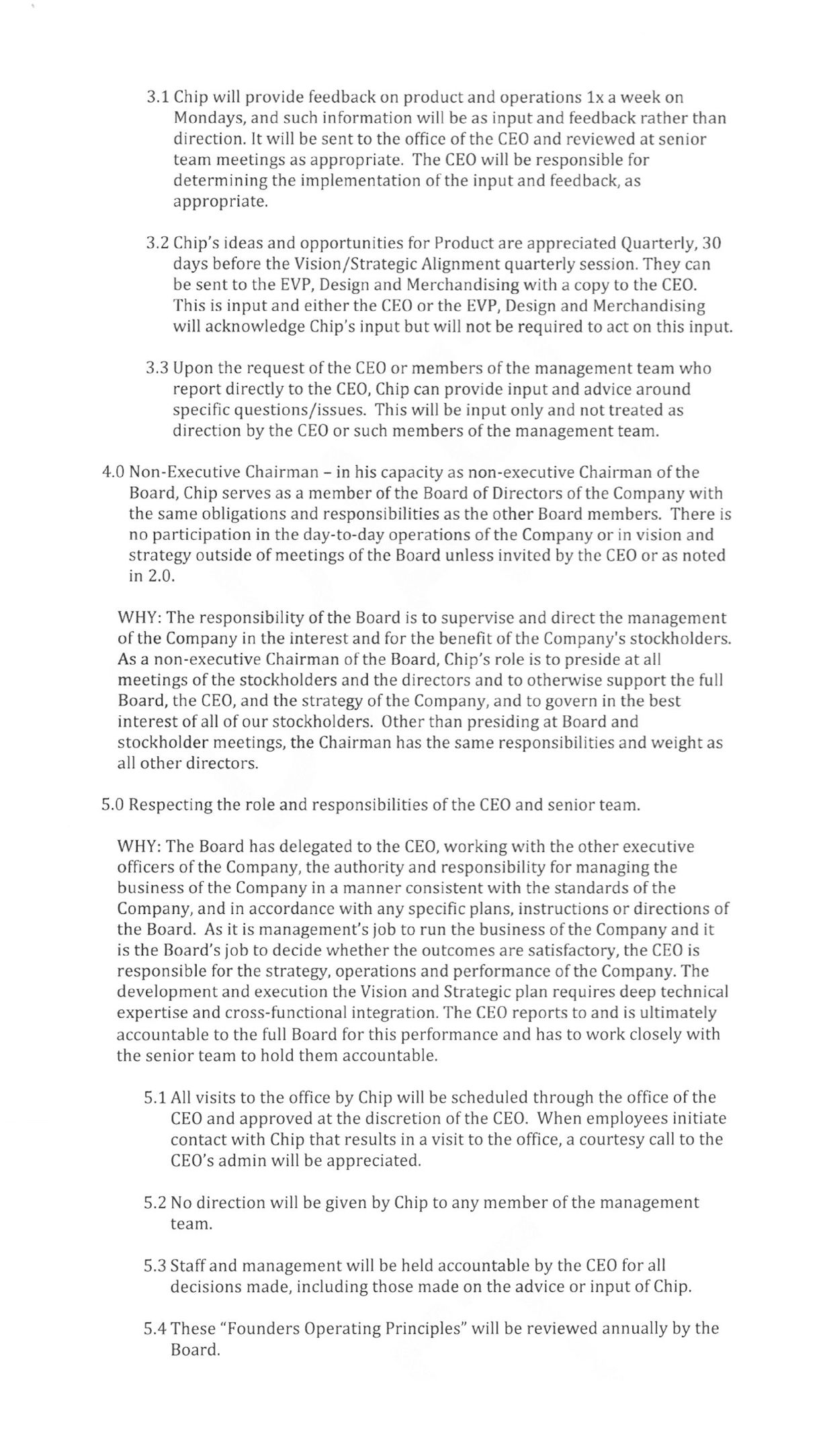

Christine then provided the directors with a document that set out the terms of my return in an at- tempt to protect her job and to keep me at arm’s length. That document is as follows:

Returning to Vancouver

Once we were back on the ground, it only took us a few weeks before we’d found out everything we needed to know.

Through a period of 30 years, I had collected samples of clothing from all over the world. Each garment had a special button, zipper, or technical apparel solution. These were samples we used to visually inspire designers. The library of samples could have easily filled a museum. But when we went to design the next season’s line, I discovered that a large portion of the best samples had disappeared. I told Marti Morfitt as Chair of the audit committee that we had a major theft issue, but she was unable to look me in the eye as she said the issue wasn’t important enough for the audit committee. Our hearts sank when we realized Christine had sold 95 percent of the samples to create space while we had been in Australia.

Still, it was good to be back. I don’t think we were alone in feeling that way. Legacy people – those who truly understood the company – were happy to see us, and we were so glad to see them. The design team was excited for the business to be potentially design-led, not merchant-led, once again.

“I was focused on keeping the business going,” says Michelle Armstrong, “so I didn’t even notice the circumstances that brought Chip and Shannon home early. My team and I were incredibly grateful when they came into the office to support us. Our merchandising team was so excited to learn the original Operating Principles from Chip, as many of them were new to the company and had not grown up with him leading the product team. Shannon had an incredible talent for giving feedback in meetings, and her sense of taste and perspective were highly-valued.”

Deanne Schweitzer says: “When we called Chip and told him we had a massive quality issue in our signature fabrics, I assume he felt that his company was being fucked up and he needed to get back ASAP and fix it. We had also gone from a culture of responsibility and accountability to a lot of finger-pointing.

“I was in a new role for the company at the time, SVP of womens. When Chip and Shannon came into the office, I personally welcomed their expertise. They were both attending our design meetings and grounding us in what made a lululemon product. Shannon would also attend fittings with the designers, which was just as valuable. The designers loved her perspective, and I loved the extra set of eyes.

“Prior to their sabbatical, Chip had written Operating Principles for the company. Many people had never worked with him before, and they were thrilled when he presented all the Operating Principles. The Product team felt energized after those presentations.

“None of this went over well with Christine. As an executive at the time, I felt the tension between Chip and Christine when Chip returned. Without saying anything, I also felt I was placed on an unspoken ‘Chip team.’ It was a stressful time.”

“It was very clear that upper management was not happy to have Chip and Shannon back on the scene,” says Jill Chatwood. “This was the beginning of the end for Christine. There was an awkward divide because you were on Chip’s team or Christine’s team and you really didn’t get to decide which team you were on. The division at the top caused fractures within the product team. The environment was tense, with direction and redirection occurring daily.”

A few days later, in mid-April 2013, I had a conversation with Christine herself. I had no plan going into this conversation. It was just five o’clock in the evening, the end of the workday, and she and I were in her office. I was just trying to re-establish a working relationship with her. As I saw it, we needed to clear the air.

In some ways, this difficult, cut-the-shit conversation had been a long time coming. We had once had a good working relationship, where we’d both brought different strengths to the table. But a lot had changed since then, and the time had come to clear the air.

Finally, I looked at her and said, “Christine, you put a lot of good things in place for lululemon, but you never had a vision for the company. Other than a three-year operational, strategic plan, who are we? We’ve got competition growing every day – how are we different from them?”

I summed up by saying, “In my mind, you’re a world-class chief operations officer. But you’re a terrible CEO.”

She cried and turned away – a reaction I thought was unprofessional and seemed fake. I disengaged and went home. To be frank, I wasn’t sure I believed her emotions. I thought she’d cried wolf one too many times whenever pressure was being put on her.

The next day, Christine announced her resignation to the Board.

1. “Lululemon Athletica Inc.,” Morningstar, accessed: August 10, 2018,financials.morningstar.com/ratios/r.html?t=LULU.

2. Tom Gara, “Lululemon Has A See-Through Yoga Pants Problem,” The Wall Street Journal, March 18, 2013.

3. Kim Bhasin, “Lululemon Pulls Stretchy Black Pants Because They’re Too Sheer,” Business Insider, March 18, 2013,www.businessinsider.com/lululemon-see-through-yoga-pants-2013-3.

4. The Canadian Press, “Lululemon Recalls Pants for Being See-through,” CBC, March 19, 2013,https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/lululemon-recalls-pants-for-being-see-through-1.1347288.

5. Stephanie Clifford. “Recall Is Expensive Setback for Maker of Yoga Pants.” The New York Times, March 21, 2013,www.nytimes.com/2013/03/22/business/lululemon-says-yoga-pants-mishap-will-be-costly.html?_r=0.

6. Kim Bhasin, “Lululemon Supplier Fires Back: Those Recalled Yoga Pants Were Not ‘Problematic’,” Business Insider, March 19, 2013,www.businessinsider.com/lululemon-supplier-see-through-yoga-pants2013-3.

7. Author’s personal records, April 2, 2013, letter from Lucy Lee Helm to Christine Day (cc: Michael Casey, Chip Wilson, Howard Schultz)